- Home

- Andrew Crumey

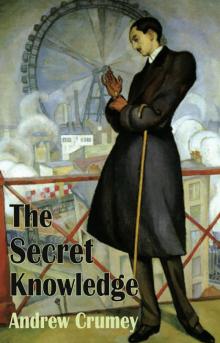

The Secret Knowledge

The Secret Knowledge Read online

Dedalus Original Fiction in Paperback

The Secret Knowledge

Andrew Crumey was born in Glasgow in 1961. He read theoretical physics and mathematics at St Andrews University and Imperial College in London, before doing post-doctoral research at Leeds University on nonlinear dynamics.

After a spell as the literary editor at Scotland on Sunday he now combines teaching creative writing at Northumbria University with his writing. He lives in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

His first novel Music, in a Foreign Language (1994) was awarded The Saltire Best First Book Prize. His second novel Pfitz (1995) was one of the books of the year for The Observer and The New York Times. D’Alembert’s Principle was published to great acclaim in 1996. Mr Mee (2000), Mobius Dick (2004) and Sputnik Caledonia (2008) followed. His novels have been translated into 13 languages.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by a grant from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, for research carried out at Newcastle University. Further work was done at St John’s College, Durham, while the author was visiting fellow at Durham Institute of Advanced Study.

Contents

Title

Dedalus Original Fiction in Paperback

Acknowledgements

1913

Chapter One

1913

Chapter Two

1919

Chapter Three

1919

Chapter Four

1940

Chapter Five

1941

Chapter Six

1924

Chapter Seven

1967

Chapter Eight

After

Copyright

1913

Paris

Yvette has been told that the big wheel is incredible, but now that she stands before it in the park there is something comfortingly domestic about its appearance. The great metal-spoked circle is like an oversized bicycle wheel, slowly whirring its passengers upwards into amazement as they stand in the blue-painted wooden carriages dangling merrily from the revolving rim. From where she watches, Yvette is unable to make out individual faces through the glass panes of those distant compartments; instead she sees the eagerness of insects.

With the warm July sunshine on her neck, Yvette waits, pricking the shadowed gravel at her feet with the point of her folded parasol. Pierre ought to be here by now; he said noon, but the clock on the tower shows ten minutes past twelve, and among the throng of people in the park, his face remains invisible to her. What could have detained him? He has never been as late as this, his delay only confirming the ominousness she detected already in the note he sent, cryptically referring to a “matter of great significance”. It seemed an implicit proposal of marriage, now it feels more like a warning of disaster. He’s had second thoughts. He loves another.

Yvette is twenty-one and already many of her childhood friends are married. Some have children of their own. She looks once more at the big wheel, slowly depositing passengers and accepting new ones from the head of the queue that snakes far behind the pennanted ticket tent. She can make out an entire family – mother and father, three children of varying heights, a grandmother or aunt – all shuffling eagerly into the stationary compartment whose door lies open for them, while the preceding passengers leave from the far side. One day, Yvette thinks, she will be the mother. One day she will have been grandmother.

When Pierre speaks of love he mostly refers to music. He is studying at the conservatory; soon, he assures her, the name of Pierre Klauer will be known around the world. She adores hearing him speak that way, though to her untrained ear his music is unfathomable. He can play Beethoven piano sonatas with the smoothness of an expert yet in his own compositions he favours harsh rhythms, jangling discords. She has always thought of art as being a matter of beauty and refinement, but the new kind is about something else, progress and modernity, even if that means sacrificing old laws of taste. He says it is the sound of the future. She only hopes there will be room in it for her.

The wheel recommences operation, revolving at its full, stately speed. The family she saw are gliding over the top, the children shoving for a better view. Yvette can imagine the commotion inside the wooden compartment, the father’s stern injunctions to order. Her own parents know about Pierre and naturally approve of him; his father has made a fortune from factories in Germany and Pierre need never work, though he has excellent prospects as an organist or teacher in one of the best schools. Any obstacle would more likely come from Pierre’s side, since Yvette’s father is only a furniture dealer who, for all that he has achieved, is in some people’s eyes no better than a shopkeeper.

It is a long while for a woman to stand alone. Eyes have been noticing her; young men tip their hats, smile, stroke their moustaches in gestures of invitation or enquiry. So many men have passed her in these extended minutes, most with a partner or friend, but others alone, like herself, and it is only her very deliberate turning away from them – at one point even waving to an imaginary far-off Pierre – that has prevented some from speaking.

She decides to wait less conspicuously, near a row of whitewashed stalls where people are tossing hoops at upright bottles, aiming darts at targets, buying cups of lemonade. Yvette places herself at the end of the row, beside a glazed booth from which candied fruits are being sold. Sunlight shines through its yellow pane onto Yvette’s dress, dappling it with light. A butterfly, impressed by the topaz glow, flits intently about her, as if trying to suck nectar from the coloured air. Afraid at first, Yvette calms her nervousness of the darting creature and watches while it briefly keeps her company before speeding away above the bobbing hats of the chatting crowd.

Pierre speaks of a revolution in art; the kind of talk they can share as lovers, but best kept from the misunderstanding ears of parents. She has spent three weeks without seeing him, the longest separation since their relationship began – and only four letters to console her. He has been staying with friends outside Paris, working on an important composition. She has no reason to doubt him.

Three young men, common labourers by the look of them, are taking turns to fling balls at a pyramid of cans, their sleeves rolled up, perspiration gleaming on their unshaved faces. Probably here after a long night-shift but still with ox-like strength, lusting for pleasure more than sleep. One of them gives her a glance before flexing his muscular arm and sending the tins flying. What would these fellows make of the new art? Brahms and Wagner failed to save humanity; how can Pierre? Yet that is his dream: to improve the world. Revolutionary music is not enough; there has to be a change in the whole of human affairs, a modulation into a new key. If she did not know him well enough she might fear he was a communist. She wonders about his new friends.

And then at last his voice. “Yvette! Thank goodness!”

“Pierre!”

After so much waiting there is a sense of both joy and awkwardness, because although his white suit and straw hat, his black tie and the flower in his buttonhole are all familiar, she thinks he looks somehow different, as though a year has passed since they last saw each other. When he bends to kiss her hand she detects his father’s Teutonic formality; there is something new in the smile he raises from her fingertips, as though he might like to bite her. His teeth are whiter than she remembers.

“I’ve missed you, Pierre.”

“It’s wonderful to see you. Let’s walk.”

Arm in arm they stroll across the park that had become for Yvette a blur of worry. “Are you truly glad?”

“Of course!”

“But I think your mind is somewhere else.”

“It has been.”

They pause at the entrance to a tent where

Pierre is distracted by the sight of a wooden dummy standing as advertisement for whatever goes on inside: a dainty female figure with a brightly painted face, like a fairy or ballet dancer, and Yvette thinks to herself, after three weeks of longing it should not be like this. He cares more about a piece of wood than about me! “Do you want to go inside?”

“What? No, it reminded me of something, that’s all.”

She can take no more. “Do you love me?”

He splutters, not sure at first if she is joking, then sees the seriousness on her face. “How can you doubt it?

“Is there another you prefer?”

He embraces her. “You know you’re everything to me.”

“Then why keep me waiting and arrive with no apology? Why be so distant?”

He looks down at his feet like a humbled schoolboy. “I’ve been working hard, creating such marvellous music.” When he raises his eyes she sees in their sparkle a vulnerability that melts her fear. “You know I’ll always have two loves, Yvette.”

“Yes, I know that.” Her mind focuses on that comforting word: always.

“I’ve begun writing a symphony.”

“How wonderful!” It means nothing to her except a sudden vision of being seated in a grand concert hall wearing an exquisite dress bought specially for the occasion, diamonds glittering on her skin. She sees herself bathed in the admiration of the elite.

“Of course it might never be heard,” Pierre adds. “It’s a private commission.”

“From one of your new friends?”

“Never mind.” He takes her hand and leads her away from the tent with a sudden light-hearted swiftness in his step that makes her giddy with relief. “Let’s laugh and enjoy ourselves, Yvette. Let’s celebrate the future!”

“Yes!”

He wants to try throwing hoops and wins a ridiculous rosette that has them both giggling. They go to the little boating lake where there is a long queue that makes him impatient, perhaps they should have candy floss instead. “And what about the big wheel?” Yvette keeps asking. “When do we go on it?” He says they must save it for the right moment.

They walk along the tree-lined avenue, and Yvette playfully demands to know more about the new music, the new friends. “Are they artists?”

“A variety of people. Dreamers and scholars; an intellectual fraternity.”

“I only hope you won’t keep disappearing to be with them.”

“I promise you, I won’t. I want us to be together, Yvette.”

“You said you were staying with them; where exactly?”

He speaks breezily. “Here and there…”

“Where?”

He can see she demands detail. “Mostly at a place near Compiègne. A quiet, peaceful house with a good piano, perfect for composing. The owner’s a man of great power and influence.”

“What’s his name?”

“I can’t tell you that, Yvette. He wants me to write the symphony, he’s paying me for it, but he doesn’t wish his involvement to be known.”

“Not even to me, your… your… friend?”

“I’m sorry, Yvette, I hate to be so secretive. Eventually you’ll understand the reason.”

“Then can you at least tell me about your music?” All her doubts are crowding back: the fine house with its wealthy owner, the colony of artists inhabiting it, even the piano and the music supposedly written on it, all seem like mirages meant to hide the single female fact that stands, a mighty odalisque, against her.

He tells her he has nearly finished composing the symphony on the keyboard but still needs to do the orchestration. “It’s called The Secret Knowledge.”

“A secret you can share with me?”

“Later.”

“But why?” She stops and grips both his hands. “Pierre, I have qualms about this.”

“Don’t be foolish…”

“I know that you do, too, I can sense it. I thought you might have found another lover, but no, that’s not what’s wrong. You’re afraid.”

“Nonsense.”

“I am too. I don’t trust your mysterious patron or your intellectual friends. What does your father think?”

“It’s better for him not to know.”

She swings away wondering which possibility is more distressing: that he has been unfaithful, or that he could have fallen in with bad company. Yvette knows about the men who want revolution through violence rather than art. “You have to leave these friends of yours.”

“Why?” He is behind her, putting his hands on her shoulders, she can feel herself flowing into his touch.

“Unless you can tell me exactly what’s going on I can only fear the worst. I read the newspapers, Pierre, I know about the problems in the world. Only the other week there was that bomb that went off and killed so many people.”

“It was in Serbia.”

“How do I know your secret club isn’t an anarchist clique?”

“I can assure you it isn’t any such thing.” He makes her turn and in his face she sees a childlike radiance. “I suppose you could say I’m a utopian, dreaming of an ideal world. Is there anything wrong in that?”

“Of course not.”

“I want us to be together in that world. Forever.” When he holds her close to his chest she thinks she feels rising inside him the great announcement he wants to make, his proposal of marriage. Not yet, though. Releasing her he says, “Let’s go to the big wheel.”

What he means is that she should stop asking questions, but while they walk to join the queue she finds it impossible. “You’ve always been lost in your ideas, Pierre, yet never so mysterious.”

“It’s only temporary, and for the best. When the time is right I’ll tell you everything.”

“And when will the time be right?”

“Soon.”

They stand waiting in line with the families, couples, excited children and quietly curious grandparents. Pierre pays at the desk they reach and receives two blue tickets he holds aloft as though perusing their authenticity. “Let’s keep these as souvenirs,” he says.

“Of what?”

“Of this moment, right now, that will never come again for us.”

She looks at them in his hand, small scraps of coloured paper, and the bad feeling is in her throat and chest, the nauseous sense of foreboding. At the head of the queue, people are being assisted into a waiting carriage, and to Yvette’s eye there is something in all of it that resembles the herding of livestock. She watches the door being locked on a mother and father and their two children. Life is weightless, a falling through an endless void she can’t quite picture or put a name to, but she senses it right now, in this moment that can never return.

She grips him suddenly. “Let’s not.”

“What?”

“I’m scared of it.”

He laughs. “It’s perfectly safe, Yvette, just look at everyone else.”

“I don’t care about everyone else, only us. Let’s go back.”

The bearded gentleman in front can be seen listening to the little crisis; his wife is speaking to him from under her broad hat but he isn’t listening, instead his head is cocked to catch the drama played out behind.

“I paid for the tickets, Yvette.” There is the faintest note of petulance in Pierre’s voice.

“I’ll pay you back.”

“I didn’t mean that. Are you honestly frightened of going up? I’ll hold your hand, it’ll be beautiful, I promise.”

“It’s not the ride I’m afraid of.”

“Then what? Please let’s do it, Yvette. It’s how I planned it in my mind. How I’ve imagined it. You know there’s something very important I want to say to you. Something that will affect us for the rest of our lives…”

She silences his lips with her fingertips. “All right. Enough, darling. Only promise me again, promise me with all your heart that it will be beautiful.”

“I do.”

Their turn arrives. The couple in front are sheph

erded into the empty wooden cabin that swings to a halt before them, then Pierre and Yvette are invited too, as well as two young men behind. It all happens so swiftly and easily, Yvette thinks, watching through the glass window while the attendant bars the door firmly shut. She grips Pierre to steady herself when with a sudden lurch the cabin moves in an upward arc, making the passengers laugh nervously. It stops again for the performance to be repeated below, and before long they have all become accustomed to this new form of transport, giving them a slowly widening view of the surrounding park with each stage of the ascent.

“Aren’t you glad?” Pierre whispers, and she nods. Did he always imagine there would be four strangers riding with them?

“I’m not afraid any more.”

The remaining compartments are eventually filled; the wheel begins to rotate at a smooth and graceful pace, bringing the enraptured riders past a summit that makes them gasp with awe.

“I feel almost like a bird!” says one.

“The people are no bigger than ants.”

Standing apart from the babble of excitement, Pierre’s observations are more considered, as though he has thought in advance of the wheel’s effect and significance. “The modern world makes everything seem small,” he tells Yvette softly, the two of them pressing against a pane to see the approaching ground, the passing sweep of attendants standing idle, the commencement of the next orbit. “Life seen from a speeding window.”

“Don’t you like it?”

“The categories of like and dislike are outmoded.”

She has heard him talk this way often enough about music, but now she knows he is referring to something else. “I suppose I must be old-fashioned, Pierre, I still believe in like and dislike. That’s why I wonder about your friends.”

“They’ve helped me see the world in a completely different manner. Not through a window at all. They speak of new laws of science: relativity, quantum theory.”

“What does this have to do with us?”

“They’ve made me realise that every moment is a decision, a test. You thought of turning back, but didn’t.”

Mobius Dick

Mobius Dick Music, in a Foreign Language

Music, in a Foreign Language The Secret Knowledge

The Secret Knowledge Sputnik Caledonia

Sputnik Caledonia